Following Marcos’ deposition in 1986, the newly drafted 1987 Constitution prohibited the death penalty but allowed the Congress to reinstate it “hereafter” for “heinous crimes,” making the Philippines the first Asian country to do so.

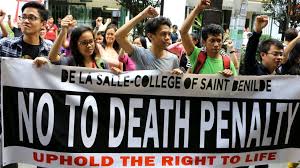

The Philippines’ deteriorating human rights situation worsened this week, as the government began considering bills to reinstate the death penalty. The House Committee on Justice’s action comes just a week after President Rodrigo Duterte used his State of the Nation Address to call for the death penalty by lethal injection for drug offenders.

For many years, the Philippines executed people, particularly in cases of so-called heinous crimes. However, under pressure from the Catholic Church, President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo abolished the death penalty in 2006. Human Rights Watch opposes the death penalty in all circumstances because it is cruel and irreversible.

Because of the Duterte administration’s overwhelming majority in Congress and ongoing efforts to promote its anti-drug campaign, the justice committee is likely to support death penalty legislation. More than 6,000 people have been killed by the Philippine National Police and thousands more by unidentified gunmen as a result of Duterte’s “war on drugs.” Accountability for these police killings, including those involving children, is almost non-existent.

Adopting the death penalty will result in more bloodshed in the name of Duterte’s “drug war,” leading the Philippines deeper into a rights-violating abyss. And the government will lose credibility and leverage in negotiating on behalf of Filipinos facing execution in other countries.

In the Philippines, the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) has stated unequivocally its opposition to the use of the death penalty. In Resolutions issued in 1991 and 1996, the Commission rejected the death penalty advocates’ arguments of deterrence and retribution, warned of the risk of irreversible judicial error, and emphasized that the solution to rising criminality lay in effective law enforcement, equitable administration of justice, and a responsive penal system.

In 1996, the CHR reiterated that the Constitution mandated it to monitor the government’s compliance with international human rights treaties, including the ICCPR, and that it would work to ensure that, in accordance with such treaties, the legal procedures and safeguards guaranteeing the rights of those facing persecution were in place.

The death penalty is not a viable solution to the serious problem of criminality in the Philippines. The certainty of arrest, conviction, and long periods of imprisonment, rather than the threat of execution, will act as a deterrent to crime. The frustration and fear felt by many Filipinos as a result of high crime rates deserve a genuine solution, not a short-term palliative offered by the death penalty as a form of retribution. A long-term reform program for the Philippine National Police, criminal investigation agencies, and elements of the judiciary is required. At the moment, law enforcement officers are too frequently perceived as corrupted or responsible for human rights violations, while justice is not seen as being distributed fairly the wealthy and influential are not treated equally in practice.

Therefore, such in preparation for the permanent suspension and eventual abolition of the death penalty, the Government of the Republic of The Philippines should take the lead in the death penalty debate by informing the public about the dangers of the death penalty. Judicial error and the disproportionate use of the death penalty against vulnerable groups The government should launch and explain a program of police and judicial reform aimed at putting a stop to crime.