The government’s efforts to halt the spread of COVID-19 resulted in numerous violations of human rights. President Duterte directed security forces and local government officials to “shoot dead” those who caused “trouble” during the community quarantine. Local officials were charged with putting people in dog cages for alleged quarantine violations.

The UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) passed a resolution to provide the government with technical assistance and capacity building. The resolution fell short of calls for stronger action to address the country’s ongoing violations.

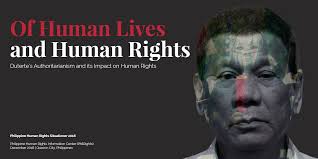

A story to tell is that the Philippines’ human rights crisis has worsened since President Rodrigo Duterte took office in June 2016, as Duterte has continued his murderous “war on drugs” in the face of mounting international condemnation.

In March, Duterte announced that the Philippines would withdraw from the International Criminal Court (ICC) “effective immediately” in response to the ICC’s decision in February to launch a preliminary investigation into “drug war” killings to determine whether a full-fledged investigation would be opened. Duterte attempted to silence his critics through a variety of means. Senator Leila de Lima, his most vocal critic, remained imprisoned on politically motivated drug charges.

The Duterte administration’s “war on drugs” continued in 2018 and expanded beyond Metro Manila, including the provinces of Bulacan, Laguna, and Cavite, as well as the cities of Cebu and General Santos. From July 1, 2016 to September 30, 2018, the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) reported that 4,948 suspected drug users and dealers were killed during police operations. This, however, does not include the thousands of other people killed by unidentified gunmen. According to the Philippine National Police (PNP), 22,983 such deaths have been classified as “homicides under investigation” since the “war on drugs” began, though the exact number of fatalities is difficult to ascertain because the government has refused to release official documents about the “drug war.”

In February, the Department of Justice issued a petition accusing more than 600 people including United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Victoria Tauli-Corpuz and dozens of leftist activists of being members of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and its armed wing, the New People’s Army (NPA). This action put those people in danger of being executed extrajudicially. Tauli-Corpuz called the accusation “baseless, malicious, and irresponsible,” and a Manila court removed her name from the petition in August. In March, Philippine presidential spokesman Harry Roque claimed that “some human rights groups have become unwitting tools of drug lords to stymie the administration’s progress.” This echoed remarks made days earlier by Foreign Affairs Secretary Alan Peter Cayetano.

Imposing drug testing on schoolchildren at a time when Philippine police are summarily killing alleged drug users puts children in danger if they fail the drug test. Mandatory testing may also violate children’s rights to bodily integrity, constitute an arbitrary intrusion into their privacy and dignity, and discourage children from attending school for reasons unrelated to any academic performance. Since the start of the “war on drugs” in June 2016, police have killed dozens of children, deaths that Duterte has dismissed as “collateral damage.” In February, police arrested three police officers involved in the execution-style summary killing of 17-year-old Kian Lloyd delos Santos in August 2017.

The Philippine House of Representatives proposed new regulations in May that would allow Congress to prohibit reporters from covering the national legislature who “sully” the reputation of lawmakers. Journalists and members of Congress have slammed the proposed rule as dangerously ambiguous and suffocating. In 2018, six journalists were assassinated by unidentified gunmen in various parts of the country.

The Philippines is experiencing Asia’s fastest-growing HIV epidemic. The number of new HIV cases increased from 4,400 in 2010 to 12,000 in 2017, the most recent year for which data were available, according to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Up to 83 percent of new infections occur in men and transgender women who have sex with men. An estimated 68,000 Filipinos are now infected with HIV. This rise has been attributed to the government’s failure to respond to the epidemic through policy. According to Human Rights Watch research, many sexually active young Filipinos have little or no knowledge about the role of condoms in preventing sexually transmitted diseases because, among other things, the government fails to promote condoms aggressively.

In June, the Philippines Supreme Court heard a long-awaited argument that could pave the way for same-sex marriage in the predominantly Catholic country. The city of Mandaluyong passed an ordinance in May to protect the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people, the latest in a slew of similar local laws passed across the country.

Therefore, The International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor announced in February that she would open a preliminary investigation into the “drug war” killings in the Philippines. The Duterte administration reacted by withdrawing from the Rome Statute, which goes into effect in a year. The European Parliament passed a resolution in April calling on the Philippines to end the drug war and ensure accountability, and on the EU to use all available means, including suspending trade benefits, to persuade the Philippines to change its abusive behavior.